In a sixth-grade classroom at High Tech High’s Middle Mesa campus, a small group of students lean over circuit boards, resin molds, and 3D-printed parts. At first glance, it looks like a makerspace. But look a little longer and something else comes into focus: these students are working on a real product for a real client.

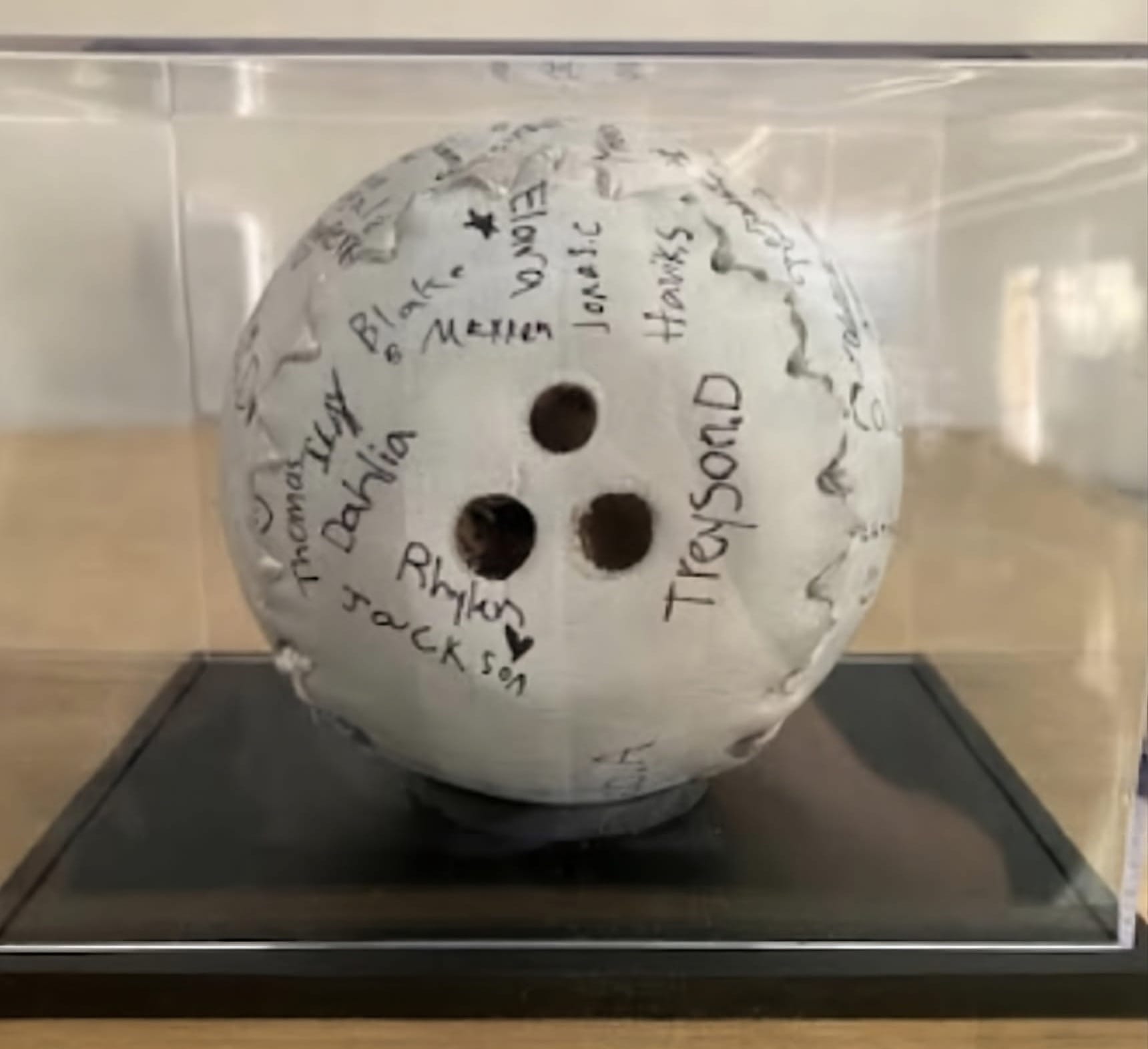

Their task is unusual for middle school. They’re building and testing components for a redesigned “Beep Baseball,” the specialized ball used in an adaptive sport for people who are blind, deafblind, or have low vision. The original technology is decades old and often fails mid-game. Supplies are scarce. The Beep Baseball community has been struggling to keep up with demand.

The need is genuine. The stakes are unmistakable. And the students know it.

Read more about our visit to High Tech High

How it started

The project began with a short video clip—thirty seconds long—that caught the attention of two teachers, David Garcia and Nathan Ewart. Both are sports fans, both are creatives, and both have a habit of treating the world like a catalog of possible project ideas. They recognized that Beep Baseball held the ingredients for something powerful: a real problem, a clear community need, and an engineering challenge worthy of their students.

The teaching partners started sketching ideas and quickly uncovered the real bottleneck: the ball itself. It was being produced in small batches by a single volunteer-run group, which meant that when balls inevitably broke, teams sometimes had to pause play until replacements could be made.

That fragility and scarcity sparked the mission. They connected with the SoCal Beep Baseball Association, drove five hours round-trip to attend a team practice, and came home with a clear goal: design a tougher ball that could be reproduced reliably and at scale, so the sport could keep moving without interruption.

Teachers and Students learning how to play Beep Baseball.

That commitment set the tone for the project. The teachers showed the students what it looks like when adults pursue an idea with intensity and curiosity. Over weekends and late evenings, they taught themselves electrical engineering, built prototypes, and laid the groundwork for students to step into genuine problem-solving work.

A Classroom that operates like a Workshop 🪚

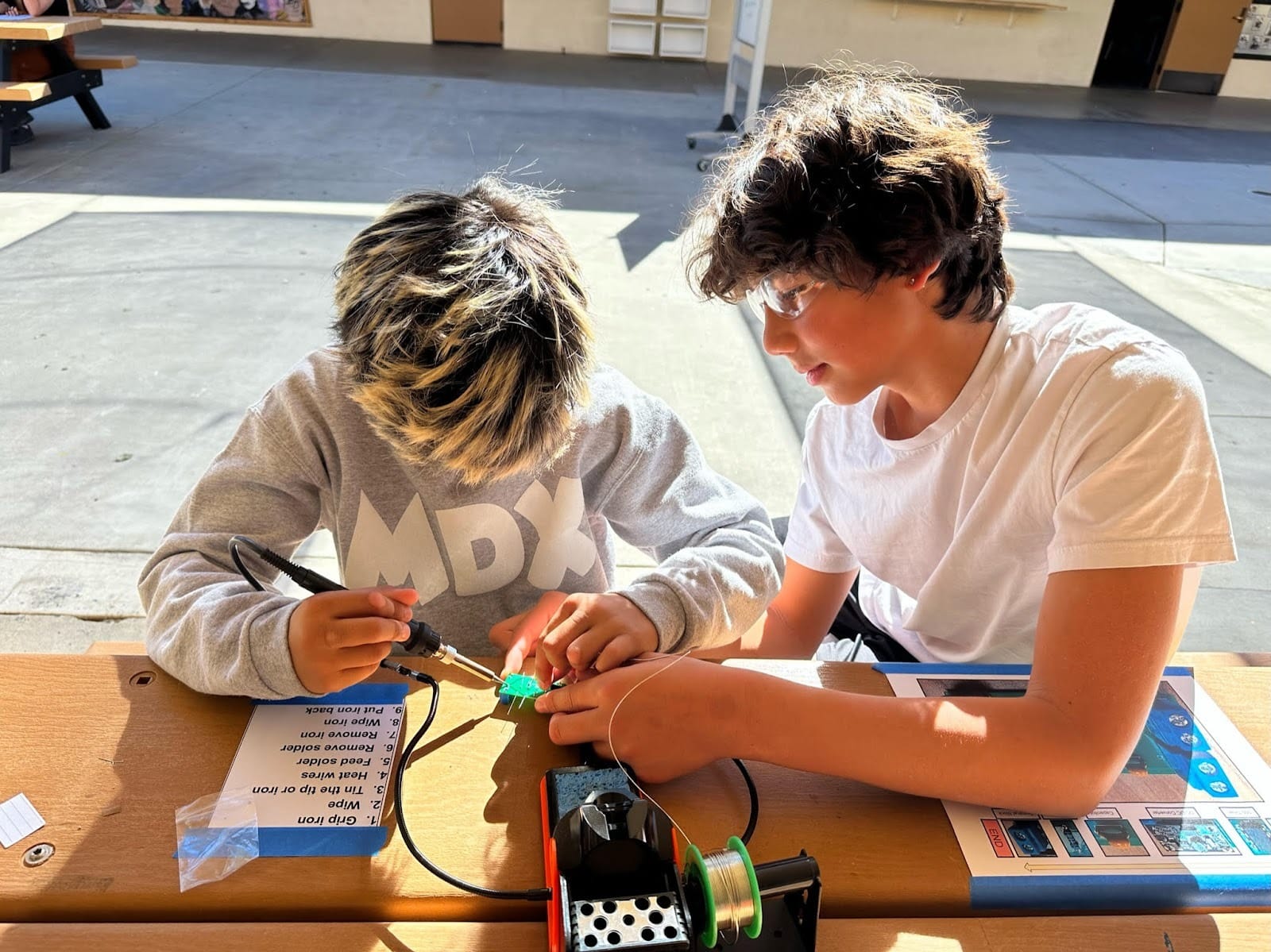

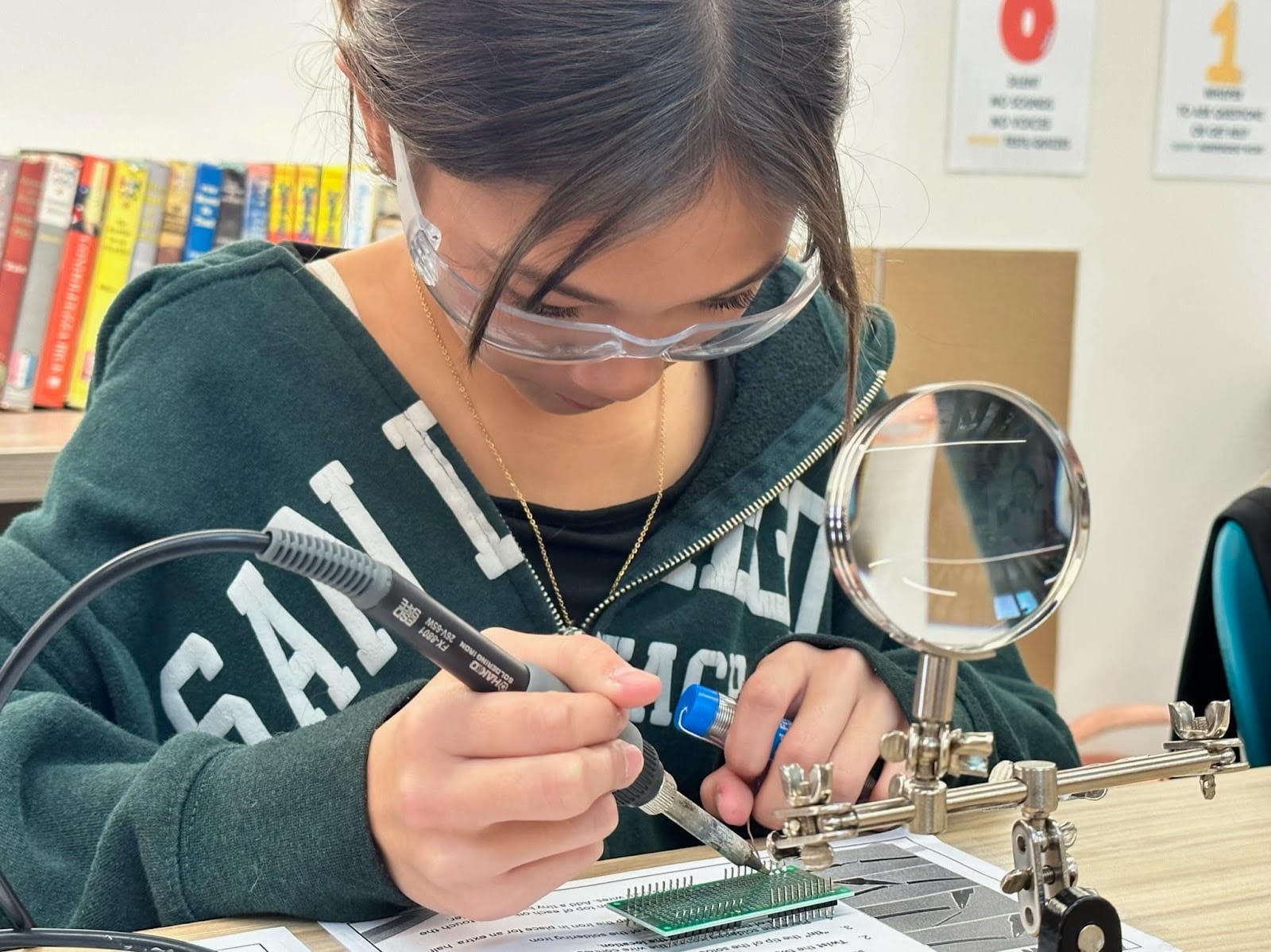

By the time students joined the project, the teachers had created a challenge that looked more like an engineering studio than a school assignment. Students learned to solder through-hole components, analyze durability failures, work in CAD, prototype parts on 3D printers, test resin mixes, and evaluate quality with the same seriousness as professionals.

The students weren’t role-playing. They were contributing to an actual design process. Their circuit boards would be evaluated for durability. Their prototypes would be part of real testing rounds. Their decisions mattered because someone else would depend on their work.

That clarity of purpose changed the atmosphere of the classroom. Students began asking different questions, taking a closer look at their own craftsmanship, and using phrases like tolerance, iteration, and failure points. They understood that their work would shape the experience of athletes who play the sport without sight.

There was excitement, but also responsibility. Students had to think like product developers, and that starts with empathy: who is this for, and what would make it truly usable and enjoyable?

Engineering for Inclusion 🧠

To deepen the experience, the teachers invited students to study adaptive design more deeply. They posed an open-ended challenge: create an enjoyable activity accessible to people who are blind. From the start, the emphasis was on understanding who you are designing for. Students practiced the empathic side of the design cycle: imagining daily realities they didn’t share, noticing where common games exclude, and asking what would make an activity genuinely fun and usable without sight.

Groups designed accessible poker sets, tactile board games, and entirely new activities with layered sensory feedback. They tested ideas against the needs of real users, learning to incorporate braille, physical texture, auditory cues, and clear rules. They discovered quickly that an imaginative idea still needed to function smoothly in practice, and that iteration wasn’t optional.

At the exhibition, people affected by blindness interacted with the prototypes. Families participated in an “investment challenge,” allocating imaginary funds to the designs that best met the criteria. Students saw their work evaluated on its merits and how well it served the people it was meant for, so the feedback carried real weight. Many groups had struggled along the way, but the students felt the payoff when their designs held up under scrutiny.

School Culture that Supports Big Work

This kind of project benefits from a school culture where collaboration is the norm. At Middle Mesa, teachers plan together, problem-solve together, and expose their process openly. It creates an environment where students see adults engaging with authentic challenges, seeking help when they need it, and iterating constantly.

The sixth graders also saw something else: last year’s students still care about the project. Seventh graders routinely stop by to ask about new prototypes and recent breakthroughs. They want to see whether the latest version survives a home-run stress test on the yard. Their interest signals something important to current students: this work has a life beyond their classroom.

Entrepreneurial Thinking 💭

The teachers never described the project as entrepreneurship, but the mindset is unmistakable. Students practiced skills that echo early-stage product development: recognizing a real need, working within constraints, building relationships with stakeholders, testing ideas, analyzing data from failures, and bringing a product closer to feasibility with each iteration.

There’s no pitch deck or profit motive, but the spirit of innovation and taking initiative is the same. The project helps students develop the habits of people who shape new solutions: persistence, curiosity, and a willingness to learn skills that didn’t exist in their toolkits before the project began.

Work that Prepares Students for the World 🌎

What stands out most is the way sixth graders rise to challenges when the work is real. They notice their teachers’ commitment, match their energy, and build things that surprise the adults around them.

In the process, they learn to think in ways that will serve them far beyond this single project:

- How to work with partners

- How to navigate uncertainty

- How to build something that matters to someone else

- How to stay with a challenge long enough to create something worthwhile

The Beep Baseball project will continue evolving. Next year’s class may tackle wireless bases or refine the resin shells. But the underlying learning remains the same.

When students engage with authentic problems and see themselves as capable engineers, designers, and innovators, school becomes a place where they practice shaping the world—not waiting for adulthood to begin.

You can learn more about how this project evolved from High Tech High.