When visitors walk into the Sea Life Aquarium at LEGOLAND California, they might not expect to be greeted by first graders. But a few years ago, that’s exactly what happened.

Clusters of six-year-olds stood proudly beside interactive displays they had designed—leading games, teaching shark facts, and helping visitors see these creatures not as villains, but as vital members of the ocean’s ecosystem. Behind the smiles and handmade artwork was something extraordinary: a deep sense of purpose. These were not assignments made for grades or bulletin boards. This was work that lived in the world.

The Spark: A Problem That Needed Solving

Every great project begins with a spark—and sometimes that spark comes from a parent.

When one of the first-grade parents, who happened to be the Education Director at Sea Life Aquarium, mentioned that their shark exhibit wasn’t keeping visitors engaged, teacher Jamelle Jones and her team saw a golden opportunity.

“What if our students could help?” Jamelle wondered.

That single question set off a months-long collaboration between the school and the aquarium—one that would immerse students in real-world problem-solving and redefine what “learning by doing” could mean for six-year-olds.

For the aquarium, it was about reimagining how visitors interact with an exhibit. For Jamelle and her students, it was about purpose—about seeing themselves as scientists, creators, and contributors to something larger than their classroom.

Building Empathy and Purpose

Before diving into design, Jamelle and her team began with empathy. They wanted students to understand not just sharks, but the broader story of ocean health.

The first graders started with a beach cleanup, learning firsthand about pollution and how human behavior affects marine life. The experience connected their curiosity to care—it wasn’t just “fun science,” it was stewardship.

Then came an official letter from the aquarium’s Education Director, “Miss Julie,” asking the students for help improving the exhibit. The tone was serious, the request real. “They felt so proud,” Jamelle told us. “It wasn’t a pretend scenario. They were being asked to do something important.”

This authenticity set the tone for the entire project. When work feels real, students rise to meet it.

Reframing Fear: From Monsters to Protectors

As the students researched sharks, one realization stood out: almost every book and video portrayed sharks as dangerous or scary. The children found this unfair.

Together, they reframed the story. Their driving question became:

“How can we, as first-grade scientists, teach ourselves and others about sharks and how they help our ecosystems?”

That question guided everything that followed. It turned a science project into an act of advocacy.

Designing with Students: Ideas That Swim

When it came time to brainstorm, Jamelle and her fellow teachers didn’t dictate what the final product would be. Instead, they asked: How do people learn best?

The students filled the whiteboard with ideas—songs, games, stories, animations, scavenger hunts. The teachers gently nudged them toward formats that could be shared publicly, but the ownership remained with the kids.

Eventually, three first-grade classes each took on a different project:

- One created both a “brain break” video and a collection of revised nursery rhymes to teach shark facts through exercise, song, and movement.

- Another designed a board game to teach about ocean food webs and shark conservation.

- A third redesigned the aquarium’s brochure, transforming it into an interactive scavenger hunt that turned visitors into explorers.

Each product reflected the students’ creativity and the teachers’ skill in balancing freedom with guidance—a hallmark of purposeful work.

Real Feedback, Real Growth

What made this project more than classroom play was the loop of authentic feedback.

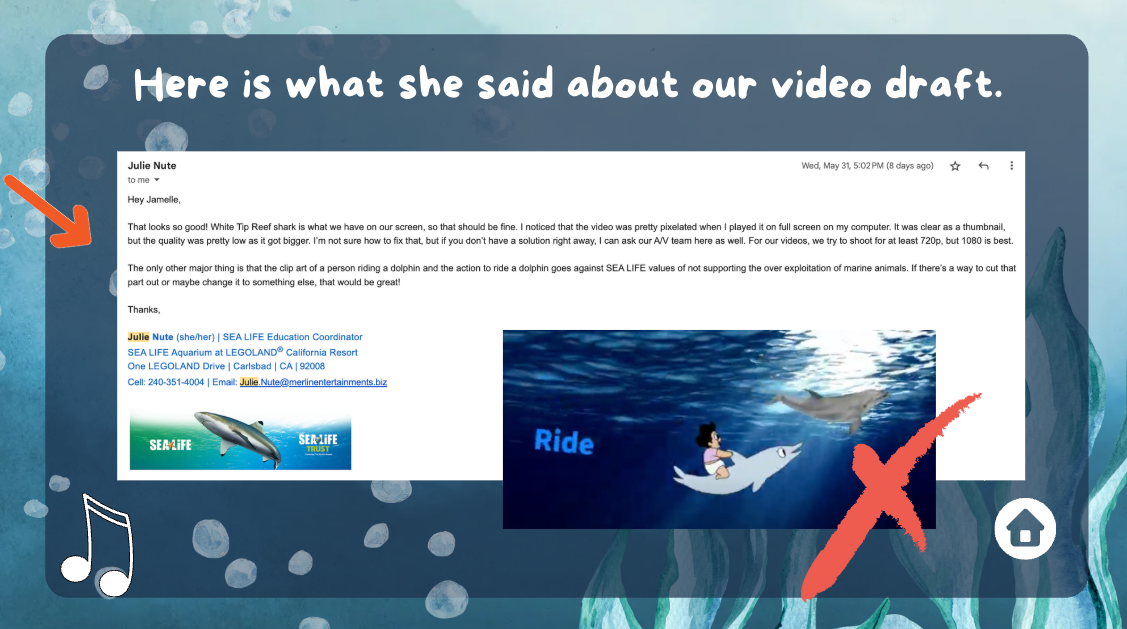

When the students submitted their first drafts to the aquarium, they expected applause. Instead, they got a lesson in professional collaboration. One animation in the brain-break video showed a child riding a dolphin. The aquarium declined to display it, explaining that it went against their ethical guidelines.

Jamelle recalled how powerful that moment was. “It wasn’t rejection—it was learning. The kids had to rethink their message and what it means to represent nature responsibly.”

The students revised the video, changing the scene to a friendly wave instead. For six-year-olds, it was a masterclass in iteration, empathy, and humility. They weren’t just learning about feedback—they were living it.

Exhibition: When Learning Becomes Public

The culmination of the project wasn’t a final grade or test—it was an exhibition. This came in two forms.

At the school, there was a process exhibition where the students shared how they created their products, their learning, and how they exhibited the work in the community.

But what happened before that is what really shines as the main event: a public showcase at the aquarium itself.

Visitors to the shark exhibit encountered monitors playing the students’ videos, tables with board games, and kids teaching adults how to draw sharks. Parents stood back, watching their children step into the role of educators and advocates.

Even years later, the project’s legacy endures. One former student, now in fourth grade, returned to the aquarium and was astonished to see the video still playing on the exhibit monitors—a tangible reminder that their work had a real, lasting impact.

Behind the Scenes: It Takes a Village

Jamelle is the first to point out that she didn’t do this alone. “It took all of us,” she said.

Three first-grade teachers, plus one science exploratory teacher, worked together across shared classrooms, coordinating lessons, logistics, and student products. They collaborated with the aquarium, families, and volunteers to make the exhibition possible.

That sense of teamwork—among teachers, parents, and community partners—wasn’t just a support system. It was part of the pedagogy. The students saw adults modeling collaboration, communication, and problem-solving, the same skills the project asked of them.

Lessons for Any Classroom

It might be tempting to think this kind of project only works in a place like High Tech High, with its flexible structures and project-based culture. But the deeper message is simpler—and more universal.

You don’t need a shark exhibit to give students purposeful work. You just need:

- A real problem that matters to someone.

- A community partner willing to engage.

- An authentic audience to share the results.

- Space for student choice and feedback loops that mirror the real world.

What Jamelle and her students accomplished reminds us that even our youngest learners can handle complexity when the work is meaningful. The question isn’t whether first graders can do it—it’s whether we adults can trust them to.

The Real Product

When we asked Jamelle what she sees as the ultimate outcome of the project, she didn’t hesitate. “The real product is the student,” she said.

Each child left the project with more confidence, curiosity, and care—for their work, for each other, and for the world beyond their classroom.

In the end, that’s what purposeful learning is all about. When students believe their work matters, they don’t just grow smarter. They grow stronger.

And sometimes, they even change how we see sharks.

You can see more of the students’ work here. And if you want to reach out to Jamelle, she is always happy to talk more about her experience with this project.