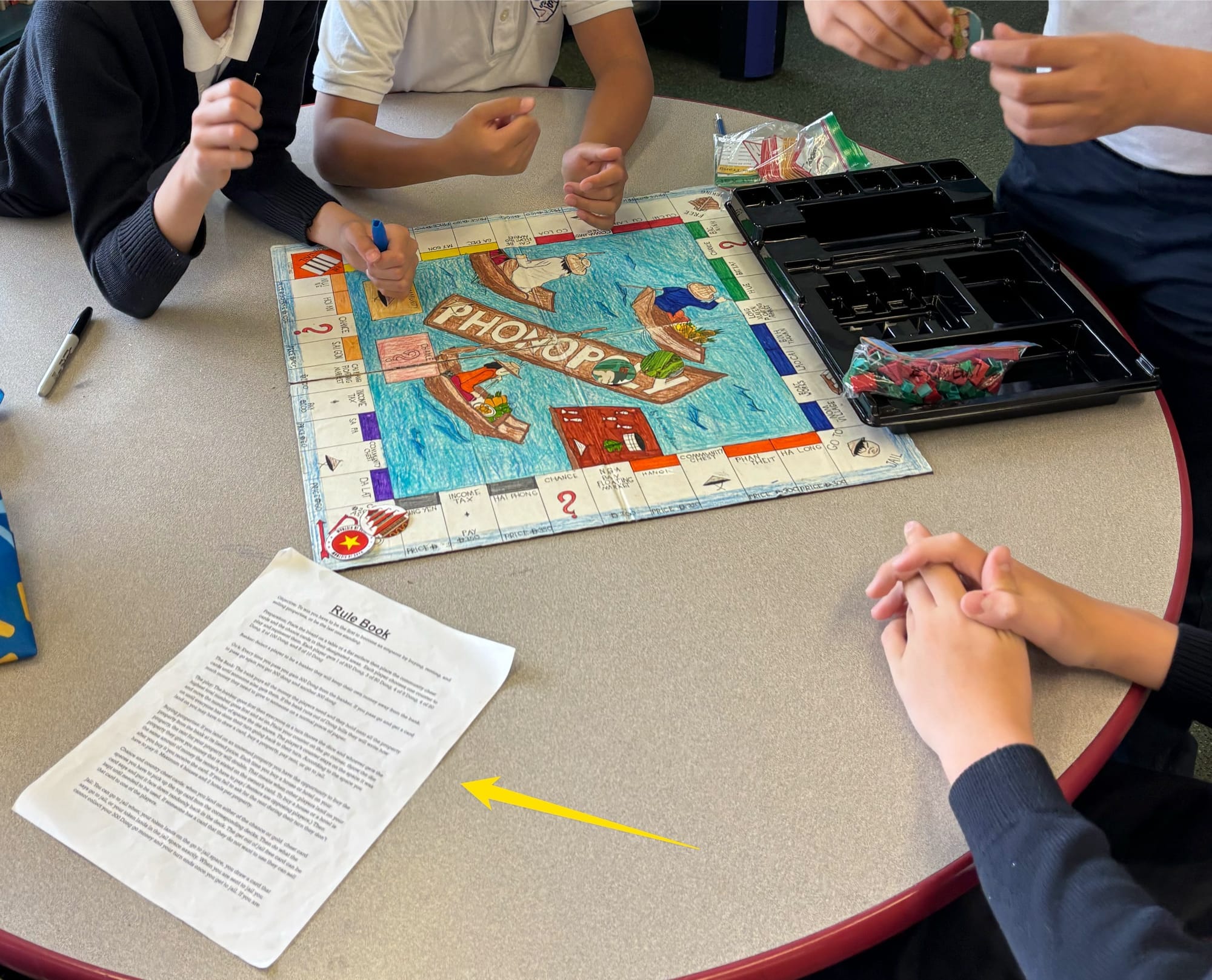

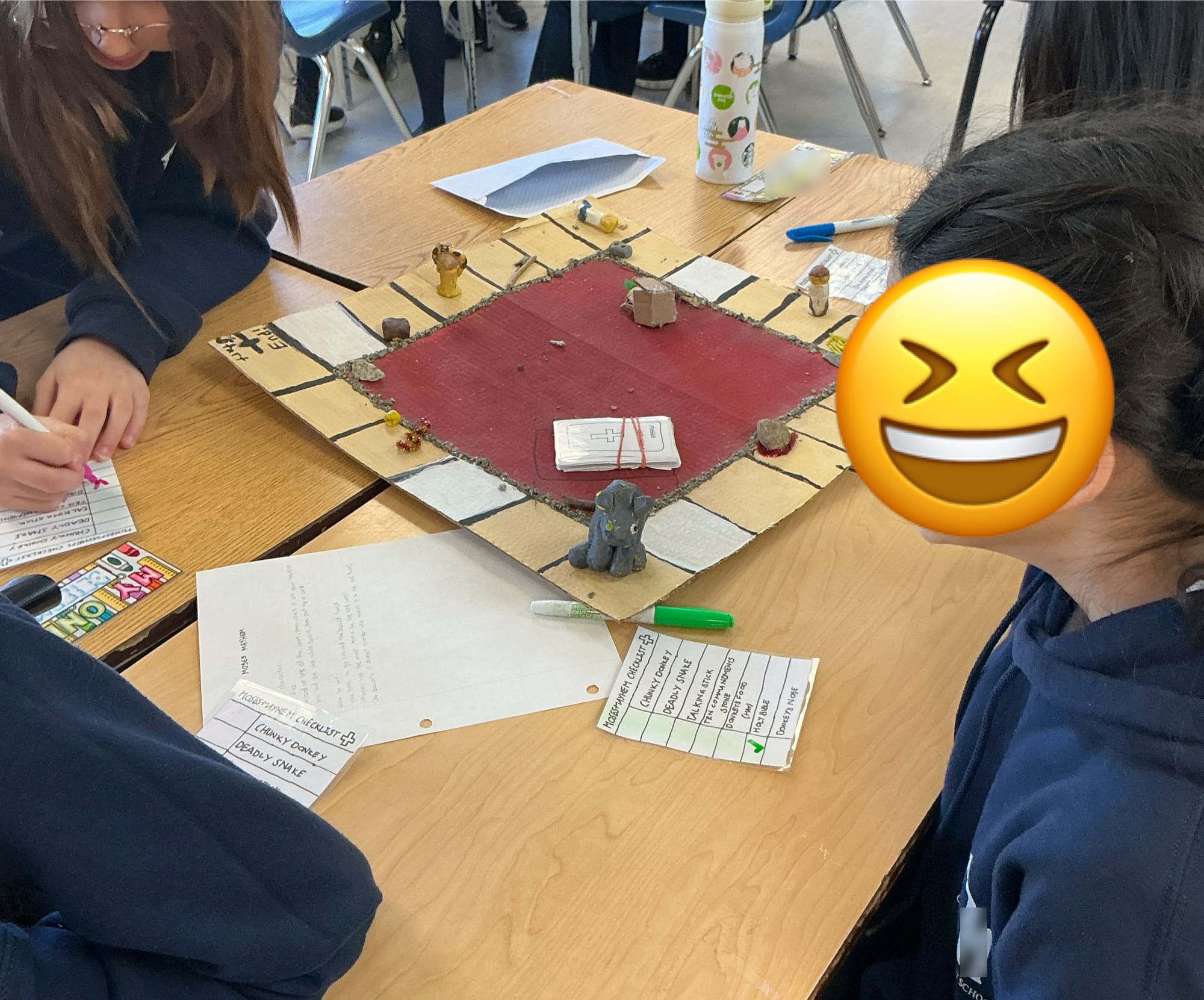

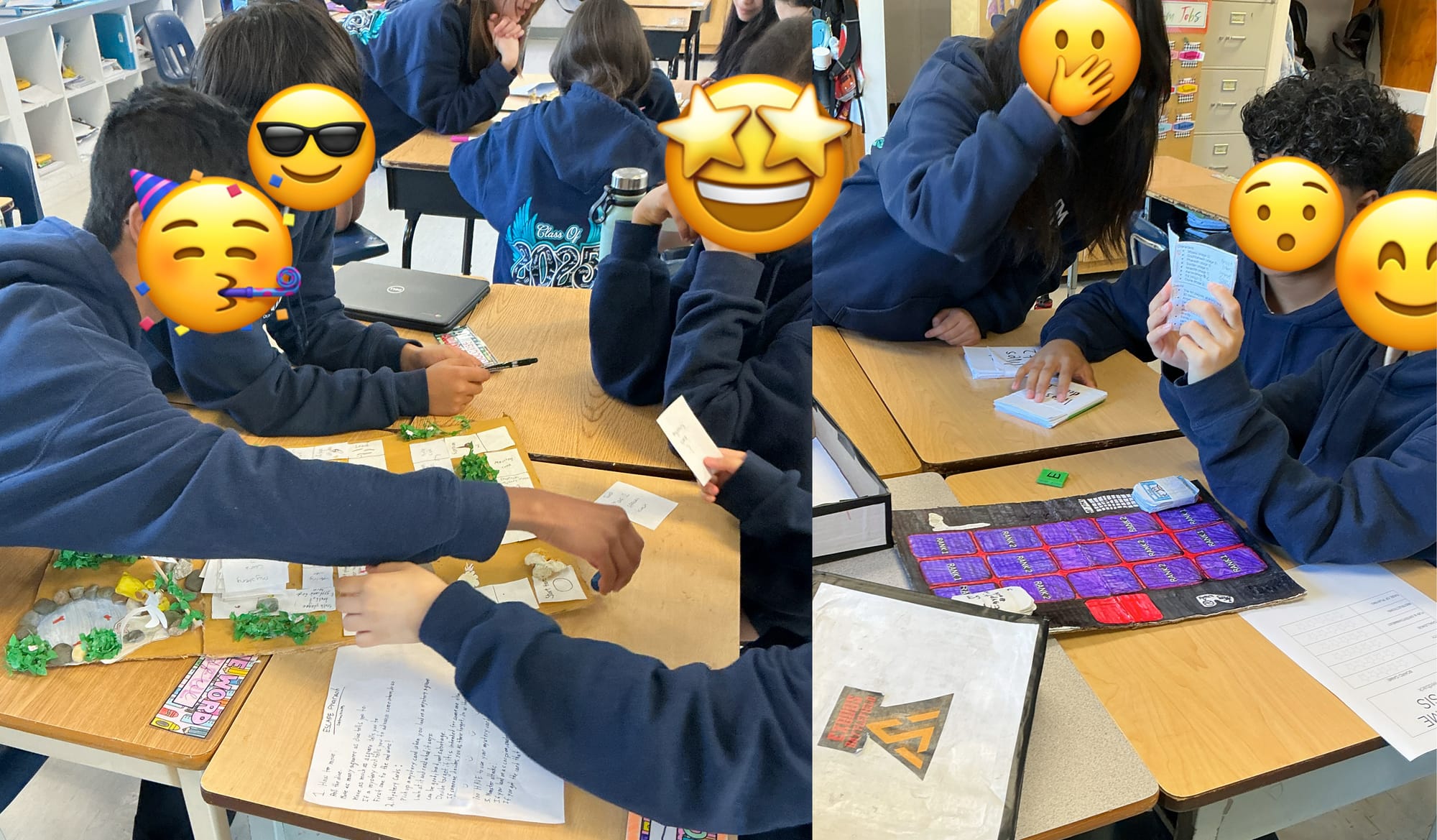

Two classrooms. Two schools. Two curriculum-linked board game projects—and one bold idea to swap them. Patricia’s Grade 7 students had just wrapped up their Ancient Civilizations game design unit, while Paul’s Grade 6s had been working on games inspired by the Book of Exodus.

Instead of keeping their projects within the classroom, the teachers swapped games—and invited each group to play, reflect, and respond to work made by students they’d never met.

In each class, the students reviewed the game’s looks, creativity, challenge, fun, clear rules, and how easy they were to actually play. Let’s see what they said.

Instructions 📋

One of the biggest takeaways? Clear, easy-to-follow instructions are absolutely critical. Some groups struggled with understanding how to play, either because the rules were incomplete, overly wordy, or assumed prior knowledge; “Like Mafia, but with Exodus” didn’t help students who had never played Mafia. In other cases, poor grammar and formatting created extra hurdles.

Students noticed when instructions were long blocks of text with no clear headings or steps. One memorable piece of feedback:

“It took forever to start because we couldn’t figure out what to do.”

Balance of Gameplay ⚖️

The structure of the games themselves sparked a lot of conversation. One game sent players two steps back before they’d even hit the board. Rough start. Still, students saw potential: “If they fix that, I’d play it at home.” Another game got tagged as “fun but way too easy. Could be good for younger kids.”

When gameplay flowed well — with a good mix of challenge, reward, and sabotage — students were hooked.

Player Interaction 🏎️

The most positive feedback by far was for games that allowed players to sabotage, team up, or outmaneuver each other. Friendly competition brought games to life, making every turn exciting.

One group highlighted a game that would be “even better with the whole class playing at once,” showing just how important player dynamics are to creating energy and engagement.

Presentation 🎨

Students also paid close attention to how the games looked and felt. Some games impressed with custom-painted boards, 3D elements, and professional-looking packaging. Others lost points for feeling “recycled,” like just painting over a Clue or Monopoly board without enough originality.

The presentation of some games even affected functionality: unevenly cut cards made it easy to guess players’ moves, and overly thick card stacks disrupted smooth gameplay.

Reflecting on the Process 🪩

Looking back, here’s what we’d tweak next time to make the experience even stronger:

- Analyze before creating - Students who spent more time studying real board games wrote better instructions and built stronger designs. They also gave better feedback! Analysis should come first.

- Roleplay as designers - Before sending games out, students could write a short “pitch” introducing their game and asking for specific types of feedback. This would give reviewers more direction — and designers more focused advice.

- Scaffold the feedback - Structured feedback forms (“I liked… I wondered… I suggest…”) helped some groups give more balanced, constructive comments. More scaffolding = better critiques.

- Focus on “friendly feedback” - Despite our best efforts, students often leaned negative in their comments. More upfront modeling and mini-lessons on giving positive, actionable feedback would help set the tone.

- Imagine bigger exchanges - This board game swap opened the door to bigger ideas: podcasts, storybooks, inventions, science projects. Imagine a network of schools where student creations travel, improve, and inspire across classrooms!

All in all, the board game exchange was a massive success.

It’s clear that giving students a real, external audience pushed them to take the project more seriously, and to think more deeply about what makes a game fun and playable.

We learned that how students approach feedback and design is shaped by the process we build around them. When we scaffold it right—more analysis, clearer asks, better feedback tools—students don’t just play games, they think like designers. And that’s the real win here. Not the fanciest board or the most sabotage cards.

It’s the mindset shift.

Austin's Butterfly 🦋

Modeling feedback can be tough when it always flows from teacher to student. Austin’s Butterfly shows how peer feedback can create a joyful, positive experience for both giver and receiver.

By guiding students to give kind, specific, and helpful feedback on six versions of the drawing, Ron Berger highlights how quality improves through revision.